What Does Manhood Really Mean? Asks Nandini Krishnan In Her New Book “Invisible Men”.

Posted byShruti B.Posted onNov 27 2018Leave a comment

In this remarkable, intimate book, Nandini Krishnan burrows deep into the prejudices encountered by India’s transmen, the complexities of hormonal transitions and sex reassignment surgery, issues of social and family estrangement, and whether socioeconomic privilege makes a difference.

Female-to-male transgender people, or transmasculine people as they are called, are just beginning to form their networks in India. But their struggles are not visible to a gender-normative society that barely notices, much less acknowledges, them. While transwomen have gained recognition through the extraordinary efforts of activists and feminists, the brotherhood, as the transmasculine network often refers to itself, remains imponderable, diminished even within the transgender community. For all intents and purposes, they do not exist. In a country in which parents wish their daughters were sons, they exile the daughters who do become sons.

In this remarkable, intimate book, Nandini Krishnan burrows deep into the prejudices encountered by India’s transmen, the complexities of hormonal transitions and sex reassignment surgery, issues of social and family estrangement, and whether socioeconomic privilege makes a difference. With frank, poignant, often idiosyncratic interviews that braid the personal with the political, the informative with the offhand, she makes a powerful case for inclusivity and a non-binary approach to gender.

Above all, she asks the question: what does manhood really mean?

Q. How big a role did/does religion play in the way the transmasculine community has been treated? And were there differences in treatment across different religions?

The pantheistic or polytheistic religions and the Abrahamic religions are very different in terms of their approach to gender and sexuality.

Hinduism, for instance, is such an informal religion, with no one book or scripture. The downside of this is that it is very open to interpretation, and is usually appropriated by bigots. The positive factor is that there are stories of gender transition in mythology – Krishna taking the form of Mohini to consummate his marriage to Aravan; Amba turning into Shikhandi so s/he could go to war with Bhishma; Arjuna living as Brihannala in the palace of King Virata, as dance instructor to Princess Uttara; Chitrangada being raised as a man because the kingdom of Manipur had no male heir. But while transwomen do seem to have a religious tradition, and command respect at certain places of worship, transmen are largely excluded. Even mythology has been subverted. People tend to see Shikhandi as a hijra rather than as a transman, for example.

Christianity expressly forbids even cross-dressing, so I imagine the Bible does not take kindly to gender transition. This is from Deuteronomy 22:5 – “A woman shall not wear a man’s garment, nor shall a man put on a woman’s cloak, for whoever does these things is an abomination to the Lord your God” – and this is from Corinthians 11:14-15: “Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him, but if a woman has long hair, it is her glory? For her hair is given to her for a covering.”

As for Islam, while homosexuality is explicitly forbidden in the Q’uran, there is no mention of gender dysphoria or gender transition. There are various disagreements among Islamic scholars, not only between Shi’a and Sunni Islam, but even within Shi’a Islam. They do all believe in the binary, but they distinguish between “internal gender” and “external gender”. Most schools of thought seem to believe gender transition is permissible only if the internal organs would also change – as in, a transwoman should be able to bear a child; a transman should be able to impregnate a woman.

Most religions treat sex as exclusively procreative and not pleasurable. And this transactional perspective is easily adopted by the righteous religious hoi polloi, the hypocrisy of condoms being used in cisgender heterosexual intercourse notwithstanding.

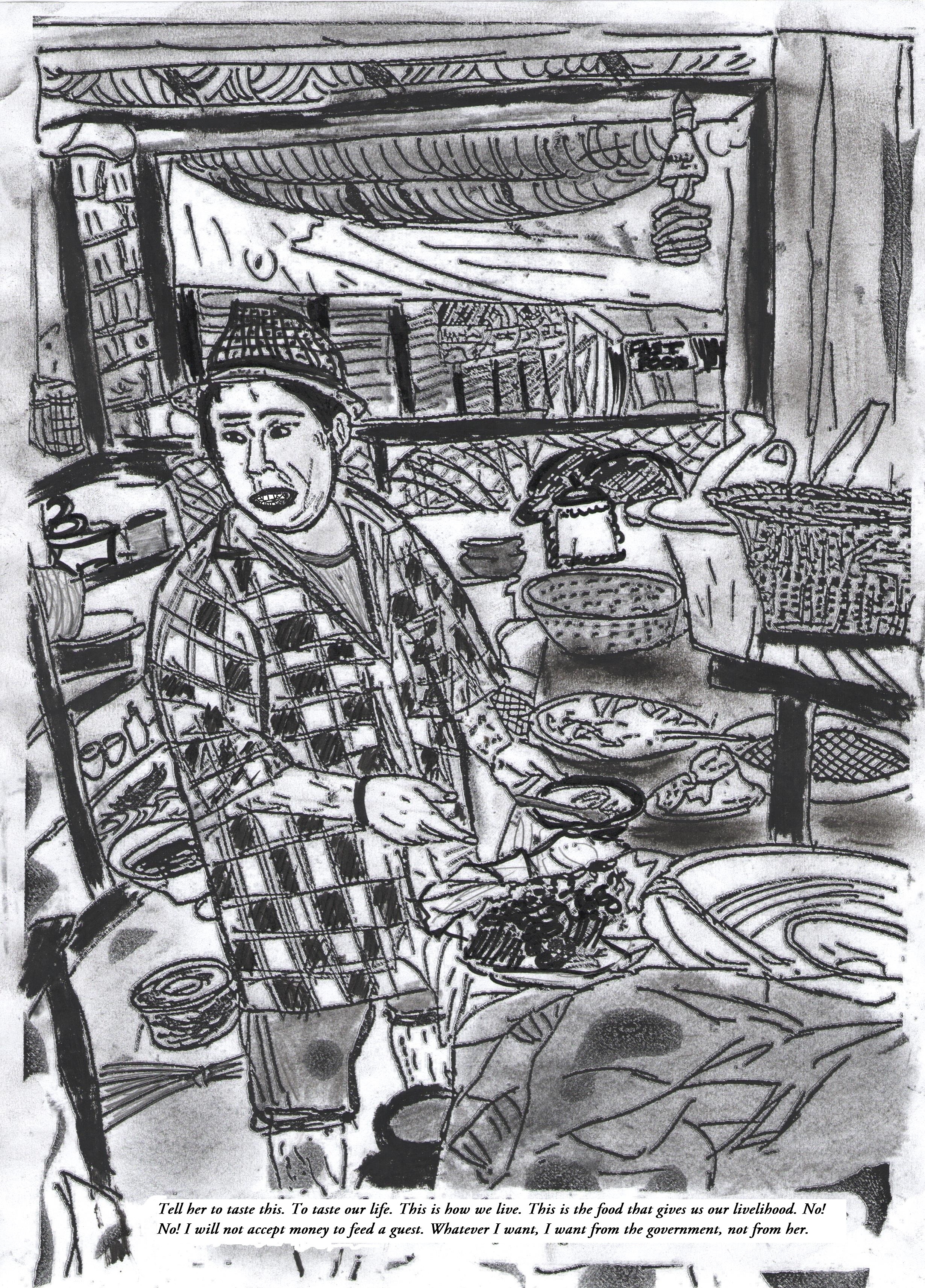

Illustration of transman Joymati

Q. I love that the stories are fragmented but still brought together based on the overarching trope of transmasculinity, and Selvam’s own journey. Is this what you had in mind when you began working on the book, and what was the thought process behind including illustrations to tell the stories?

Thank you, that’s very kind. To be honest, I had no clue how to structure the book, and I’m grateful my editor Manasi Subramaniam didn’t run away when I sent her my first draft. She asked me to rethink the structure, and when I thought about my takeaway from my research, three things came immediately to mind – one was the idea that the community is so invisible; another was the intense longing for transmen to be seen as men and not as “female-born”; and the third was how each story had left such an impact on me, and how personal my interactions with my interviewees had become. Just as our memories of interactions with our loved ones are fragmented, the narratives I had heard and recorded and transcribed became fragmented too.

Often, the most poignant statements would be made by my transman friends or their partners when I was not interviewing them, when my recorder was not on, when we were walking somewhere or waiting for someone or cooking a dish. And since most of us perceive things visually, it left me with images in my head that I wanted to convey to the reader.

I would like to share the story of the first illustration. I was in Imphal, and we had gone to a food shack run by a transman called Joymati. He took a quick break so I could interview him, and then made a plate of food for me. Speaking through an interpreter, he said, “Ask her to taste this. This is our life. This is how we make a living. She will be tasting our life when she eats this.” And when I reached for my purse, he said, “No, no, you are our guest. We don’t want your money. Whatever we want, we want from the government.” I couldn’t get that image out of my head – the expression on his face, the food his wife had prepared, the ingredients stocked in the shack, how his words seemed to hang in the air, mixed with the smell of the meal. There is a story behind each illustration.

Q. How did your own experiences and understanding develop as you worked on the book?

I think the closest comparison I can make to the lay experience is that it is like learning a new language. You know how, at first, you have no clue at all? And then you take baby steps, and suddenly you realise that you have begun to understand the language? But speaking it is still a challenge. And sometimes, you find you don’t have the vocabulary and you need help. And you suffer the frustration of not being able to translate your thoughts and find the right words to express yourself. Now, imagine having to tell a story in a language you are just learning. Do you have a right to that language? Are you appropriating it? Are you offending the native speakers of that language?

So that’s kind of where I am with understanding transmasculinity. When something is not a lived experience, I’m not sure you can ever wholly understand it. And as a ciswoman writing about transmen, I am still learning. I find I can relate to transwomen far more easily than to transmen, because their femininity creates an immediate bond.

But I did notice that initially, I don’t think I saw transmen as men – I saw them as having the same biological organs and functions as I myself did; when I got deeper into my research and when I interacted more with transmen – many of whom were extremely flirtatious – I began to see them as truly masculine. I could sense a certain vibe in them, which is pretty much the same as cismen, particularly heterosexual cismen.

Q. Organisations like the Anubhuti Foundation have been doing some work with LGBTQIA+ individuals and addressing mental health problems. Any advice from your discussions with the community on how organisations can reach out and aid the transmasculine community?

I think the issues of mental health and addressing mental illness have been severely stigmatised in this country. LGBTQIA+ individuals are understandably wary of psychiatrists, particularly because their orientation or gender identity itself has been considered an illness or abnormality by their families; even medical journals, including the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, until recently classified transmasculinity or transfemininity as a “disorder”.

Scientific research into what causes gender dysphoria is ongoing. Every now and again, there is a paper which says there are similarities between the brain of a transman and a cisman, or a transwoman and a ciswoman.

When so little is known, I think the most important thing one has to do is to clarify why someone even needs aid – the mental health issue is not one’s sexual orientation or gender identity; the mental health issue, particularly depression, is caused perhaps by the pathologising of one’s identity, by how society receives one, by how family treats one.

Organisations or individuals who want to help the community might do well to ask people from the community what aid they actually need. A crucial contribution would be suggesting doctors who are well-informed, who are broad-minded, who will not suggest that someone can be “cured” of gender dysphoria through marriage or pills.

Q. From your interactions, were there any suggestions that came up about how the media should approach discussions surrounding the LGBTQIA+ community, specifically the trans- and intersex communities?

Oh, yes. My god, yes. A transwoman friend of mine, Santa Khurai, pointed out that any article on LGBTQIA+, even on gay rights, is accompanied by two nude or semi-nude men making out. She said in a quote I love in the book, “Sex, sex, sex, sexual orientation, sex, sex, sex” – this is all media coverage of the community boils down to. And even if the article has nothing to do with sex, readers are left with a sexualised image.

Several points would come up often when I discussed media coverage with my interviewees.

First, the media is not too well-informed about the difference between transgender and intersex people.

Second, there is an unhealthy curiosity about the process of transition itself – in terms of before-after pictures and one’s dysphoria about the body, and the process of medical transition, particularly to do with surgery.

Third, the media is obsessed with love stories involving transpeople and cispeople, and sappy articles about couples, usually peppered with misgendering, are very common.

A related problem is that the media also feels entitled to highlight the sex lives of the LGBTQIA+ community. Many couples whom I interviewed would tell me journalists often asked them how they had sex. Some people may want to share these stories, but then they narrate them of their own volition – for instance, a transman I interviewed told me he wanted to make it clear that he had never been pleasured as a woman by any of his girlfriends. I didn’t ask any further questions, because I don’t have a right to know, and to be honest, I’m not too curious about other people’s sex lives.

The media has to understand that the conversation must evolve beyond the body, and beyond romance.

Even when I am being interviewed about the book, most journalists are interested in what I learnt about the sexual identities and sexual freedoms and sex lives of transmen.

A challenge I had to face while interviewing transmen, particularly those who had interacted with the media, was one I didn’t quite anticipate – some would reel off a particular version of their story, somewhat sensationalised, because that was what they thought I wanted to hear. It took many interviews and many interactions before I could convince them this was their story, not mine.

Q. Were there any glaring differences in transmasculine experiences in different age groups? If so, what were some examples?

Most of the transmen I met were quite young. I did meet a few transmen in their fifties, and their challenges were very different. For one, they grew up at a time where the internet was unheard of, and there were no social networks and therefore no support groups. Information was extremely hard to come by. Sex reassignment surgery was a distant dream, if it was even a dream. They had no role models. Many older transmen had grown up believing they were aberrations, that there was something wrong with them. They had to fight for the most basic things – to avoid being forcibly married to cismen, to get ration cards or Below Poverty Line cards, to find houses, to find jobs. A transman-ciswoman couple I interviewed, who are in their early fifties and have been together for nearly three decades, told me they are worried about who will care for them when they are old – they will not pass an adoption check; they cannot depend on their nieces and nephews. Transwomen have their chelas. Whom do transmen have to whom they can turn?

Younger transmen do have a more robust support system. Many of them know they can access surgery, and are thinking not just of adoption, but of having biological children by freezing their eggs. Information is accessible, and the world is slightly less prejudiced than it was a generation ago.

Life is not a breeze for young transmen either, but it was much, much harder for their older counterparts.

Q. What were some fears and hiccups you dealt with while you worked on this book? You address some inhibitions in the beginning of the book, but was there anything specific you had to deal with while working on this as a cisgender female?

Mostly, I constantly questioned whether I had the right to tell these stories. I had to be wary of “othering” my interviewees. I also wanted to make it clear both to them and to the readers that I was not looking at them as specimens in a study, but as human beings with a narrative.

I think the specific problem I had was that I was writing about an experience I had not lived. In a way, it was an advantage, because I could approach them with a tabula rasa. But I felt extremely uninformed, vacuous, and clueless at times. No writer likes feeling that way J

Also, as I said earlier, I can relate to transwomen – I’m very much in love with my own femininity, and I cannot stand my baby pictures, in all of which I have a pixie haircut, or my childhood pictures in which my cousins and I are cross-dressed because our mothers thought it was adorable. I shudder at the thought of having male organs, and relate to the horror of transwomen and their keenness to discard those. It’s harder for me to understand the transman’s horror at getting a period or growing breasts at puberty. Perhaps a cisman would be able to relate far more easily to transmen than I do.

You can buy a copy of Invisible Men on Amazon

Tags

BooksFeaturedGenderIndiaInterviewsTransgender

Share

About the author

Shruti is a writer and designer who has a hard time writing about herself. She is passionate about feminism, mental health, good art, literature, and puppies. When she’s not daydreaming about Harry Potter, she can be found trapped in a YouTube blackhole, or impulsively buying more books than she can read.

Leave a Reply