Courtesy: Multiple Facebook posts on which I have been tagged. (If someone knows the photographer’s name, please tell me, so I can put in a credit line.)

I had said earlier that I would share all reviews, negative or positive, from anyone who has read my book, Invisible Men: Inside India’s Transmasculine Networks. Following a week of my enduring constant tags on social media, threatening and abusive phone calls in various languages from various numbers, and exhausting WhatsApp conversations, one of my detractors finally claimed to have read the entire book.

After initially calling for the book to be banned, Gee Imaan Semmalar has written a piece on The News Minute which is categorised “Book Review”. The writer of this piece makes several assumptions about consent and has extrapolated the implication of certain sentences. There are factual errors in the piece that indicate he has not read the book with attention, besides the vicious personal attacks on several people mentioned in the book, including me. This is my response to his piece.

Gee Imaan Semmalar has called my book “factually incorrect”, which is not true:

He writes:

“For instance, in the Preface itself, the author claims that 2016, which was when she met Selvam (one of the key participants in her research), is when transmasculine networks were beginning to be formed in India. We have had trans masculine networks in India for more than two decades. A fact that the author herself mentions in the book when talking about Sampoorna, a network for trans and intersex people being formed in the late 1990s.”

My response is:

This is not my claim. It is my takeaway from an interview with trans rights activist Satya Rai Nagpaul, which was published both in Fountain Ink Magazine, March 2017, and in Invisible Men, and I have attributed the statement to him in the book. Satya spoke of how transmen have found each other in several cities over the last two years and various networks were being formed through WhatsApp and Facebook. Satya told me Sampoorna had been formed in the late 1990s, but detailed the growth of the network over time, which I have included almost verbatim in the book.

Also, I first met Selvam in 2006.

The following loaded statement has been made by Gee Imaan Semmalar:

The author for the rest of the book transforms into a detective constantly viewing and describing our bodies/gender expressions and giving her own unsolicited opinions on how “feminine” or “masculine” we are, with a generous topping of caste prejudices.

Who “solicits” anything from the writer of a book? Perhaps the publishers? Perhaps the editor? Even so, the decision to write is the author’s.

As I say in the book, I had initially pitched Invisible Men as “an anthology of individual narratives, but my discussions with my editor and publishers had changed the form the book was to assume”. I ask in the book, “Perhaps there was something to be gained from the readers fumbling through the topic with me. Could a case be made for my being equipped to enable the readers to interrogate their own prejudices, as I did mine?”

This is precisely what I set out to do, and I will elaborate on this through the piece.

As for the unqualified “caste prejudices”, I cannot respond at this juncture, since they are, well, unqualified.

The foreword by Manu Joseph:

Several transpeople took issue with a sentence in the foreword by Manu Joseph, and Semmalar calls it “the audacity of a cisgender, dominant caste heterosexual man”.

My own take on the foreword is elucidated here:

I have great respect for Manu Joseph as a person, an observer, a writer, and a reader.

One of my reasons for requesting him to write the foreword is personal – I owe much of my love for long-form writing and my confidence in it to him.

But the other is this – Manu Joseph says what other people think, but are afraid to admit. He is intrepidly honest, to the point most people believe he is intentionally needling them. He would be offended if I said he doesn’t occasionally do so, but I think he does it most often because, in his words, he “know[s] hypermorality is a mental illness”.

In a world where every considerate post comes with a trigger warning, and the inconsiderate fire rounds thoughtlessly, it is important to say it like one sees it, and I don’t know anyone who does so more honestly than Manu.

Transpeople don’t need a cisperson to interpret transmasculinity. But laypeople do. And the only way to start a dialogue is to lay it all bare, expose our understandings and misunderstandings, our prejudices and realisations, our learning and unlearning.

At my book launch in Starmark, Madras, a stranger who had bought the book asked me as I was signing his copy, “Are these women beautiful?” I asked, “Which women?” And he said, “As in, before they become men, are they beautiful women?” I said, “That’s a strange question; why do you ask?” He replied, “I wonder whether they become men because they are not happy with how they look.” I asked him to read the book and get back to me on what he thinks. He bought the book, so I assume he will. And I hope he will never have to ask that question again once he has read the book.

The book contains several perspectives, including mine; the foreword contains Manu’s perspective, based on his own experience covering the Koovagam festival and on his reading of the book.

I do feel sorry if anyone reading any of these perspectives is triggered or hurt by them; but the hurt is unintentional. An apology is an admission of guilt or error. One cannot apologise for current understanding, and the promise of better understanding over time. I have made myself vulnerable in the book, and am examining my own understanding at every stage.

Everyone’s words are reported as they were spoken, written or felt, naked and without diplomacy. That is honest and authentic, and that is what I want the book to be.

Gee Semmalar has listen ten reasons my book is offensive. I will respond to each:

- “Misgendering and deadnaming”:

Semmalar writes: “The author paraphrases from Living Smile Vidya’s autobiography I am Vidya, in a section and uses her deadname and male pronouns to talk about her in the past.”

I read Living Smile Vidya’s autobiography in the original Tamil. In it, while recounting her childhood, she refers to herself using male pronouns and by her given name. It was in paraphrasing this section that I used those pronouns and that name, and made it clear that both were disowned by Vidya after. The title of the autobiography, as well as its translation, does contain Vidya’s given name.

Semmalar writes: “The author misgenders Rumi, a trans person who insists that no pronouns be used in the book for Rumi. The author writes Rumi’s dead name multiple times in the book and misgenders as ‘she’ when talking about the person in the past.”

I did respect Rumi’s decision not to have any pronouns used, and went with “R” in place of pronouns, a fact Semmalar has not mentioned. Rumi has read and approved every single word written about R in the book. There are two occasions where I refer to Rumi by R’s given name – one is while quoting from a paper authored by R and Sunil, which was published under R’s given name. R and Sunil requested that I mention that R now goes by “Rumi Harish”, which I added immediately. The other reference was a quote from a documentary by Chalam Bennurkar, which was made when Rumi identified as a ciswoman and used R’s given name. The quote contains the sentence: “You and I might get jobs outside, but what about transpeople?”

When I met R, I did not know R’s name had changed to Rumi. In all our interactions by text, phone, and email, I had addressed R by R’s deadname, and when I came to know about R’s gender identity, I apologised. R told me it was very recent, and I need not be sorry since I had not known.

We also discussed the quote when I sent my first draft to Rumi, and I asked whether it would be all right to use R’s given name in that section since R had identified as cis at the time, and then write about R’s new identity now.

Rumi also looked at the final draft and told me on the phone that R approved. I don’t know if Semmalar spoke to Rumi before writing the “review”. I have reached out to R myself, and will update this piece once I hear back.

- “Infantilisation of trans men”:

Semmalar writes: “Her description of a Dalit trans man as ‘like a student from a state corporation school’, is imbued with casteism, among many other such examples.”

The actual sentence is: “Wearing khaki shorts and a yellowed, once-white shirt, he looked like the student of a state corporation school.” Khaki shorts and white shirts were the standard uniform of Tamil Nadu corporation schools in 2006, and for some years beyond. Typically, students would wear the white shirts until long after they were yellowed, because the state was not particularly efficient in distributing new uniforms.

I did not know the transman’s caste until Semmalar mentioned it. I do not, as a rule, ask anyone’s caste, and only mention it if they explicitly ask me to do so, as Kiran did. So I do not see how this is “casteist”.

Semmalar has taken issue with my describing the appearance of some transmen as “Peter Pan-like” and “cherubic” and posted screenshots of my references to them as having “hairless faces” and “high-pitched voices”.

All of these had to do with my own perceptions, which I was constantly dissecting and interrogating. I will elaborate on these when I speak of sexism among transmen in the next section.

I specifically described Rommel (the name by which he goes in the book, and not his real name) as having a “cherubic” face. Rommel and I have a special relationship – I consider him my brother, and he calls me “Didi”. Like everyone else in the book, he read everything I had quoted from our interactions and everything I had written about him, and had a good laugh at my referring to him as “cherubic”. He approved the section, and I think he has the information and agency to decide for himself.

We have been in touch since the nastiness over the book began, and Rommel has been very supportive.

- Transphobia

This accusation is among Semmalar’s most baffling. I’m compared to “a character in a bad Manoj Night Shyamalan film”. Semmalar writes that I look at “ghosts of [their] past and conjure up images that violently deny [their] identities.”

He particularly takes issue with one section, where he has withheld the person’s name, and so I will too. He has only mentioned the underlined part in his piece:

“Something about their life filled me with mixed emotions— it was somehow uplifting and heartbreaking at the same time. As <retracted> kicked a stone aside and got into the car, keeping his legs slightly parted as men do, I had a sudden image of him in a sari, with long hair, pregnant and grinding chutney in the morning. All I wanted for this little family is that they should be happy and safe, I thought.”

This “image” is a reference to an earlier section, where <retracted> had narrated a terrible experience to me, the inclusion of which in the book he did approve:

The section reads:

‘I was biding my time. When I was seven months pregnant, I had a window, when they had all gone out. I slipped out to a public telephone and called my mother. I asked her to advance my valaikaappu’—a function where a pregnant woman is given glass bangles, and eventually sent to her maternal home—‘and to take me back. I didn’t think either I or the baby would survive another two months of this torture.’

When his family arrived, on the morning of the function, they found <retracted> bent almost double at the manual churner, grinding chutney. <retracted>’s sister was in tears. They could not wait to take him home.

In the last stages of <retracted>’s pregnancy, he faced a terrible dilemma. <Current partner of retracted> was visiting her friend one street away from <retracted>’s mother’s home. She asked him to come over. It would be their first meeting in years. But <retracted> could not bring himself to go. ‘We had been boyfriend and girlfriend. She saw me as a man. And now, here I was, pregnant from another man. It would be too humiliating. I felt tense, guilty, disgusted with myself. I can never forget that moment.’

I have since spoken to the transman in question. Before the book went to print, I had sent him the entire section on him, and said I could either translate it into Tamil, or he could get someone he knew better and trusted more to translate it for him. About a week later, he told me he was happy for me to carry everything I had written, and that it was exactly as he had told me. When I interacted with him last week – I had reached out to him as I did to all my interviewees after the trolling began – he asked me whether I had written that I saw him as female, because that would be very upsetting. I told him I did not. By “image”, I meant “memory”. Language lends itself to various uses, and the memory did appear as an image before my eyes. I did not “see” him as female. Far from it. I was disturbed by the idea that he had been forced to wear female clothes and forced to assume a female role. I think that is evident from what I have written in the paragraph quoted. He is someone I respect and like, as is his partner. His poetry affected me deeply. It is cruel to misinterpret my words to him, with the notion of tarnishing my work. I have no problem with someone making an accusation – if it is unfounded, I can dismantle it. But how can I prove to <retracted> that I don’t see him as female other than assure him of it? It is cruel to make him think I do, because it affects him more than it does me.

Semmalar writes that I am obsessed with my interviewees’ surgeries, that I ‘sniff out [my] own perceptions of femininity’ and ‘hand out [my] own progress reports of whether [they] “pass” as men or fail miserably.’

This is extrapolation. I have not spoken of anyone “fail[ing] miserably”. I have written of my own perceptions, and been honest.

Semmalar writes:

Meanwhile, here is a feminism 101 class for the author who writes: “Did I dismiss the possibilities of sexual violence from them because they lacked the organ most women have been taught to dread?” Sexual violence is a crime of power. Not biology. “Most women” dread which organ? Damn “most women”, you better make a lesbian island soon. Oh, also, trans men don’t lack anything. We are strong. We are beautiful. We are enough.

I write that “most women have been taught to dread” an organ that transmen lack. I did not say “most women dread” it. I was simply interrogating whether I had internalised certain notions of sexual violence. Would I be able to chat comfortably with a cisman who had been described as “cannot control himself around women”? Why or why not? And what made it possible for me to be comfortable with a transman who was described in that manner?

I don’t see why “most women” must “make a lesbian island”. What is the implication of that suggestion by Semmalar?

When I speak of “lack”, I mean it quite literally, and am not implying it is a flaw. I have not said anything to contradict these sentences: “We are strong. We are beautiful. We are enough.”

Every time I have pointed this out, I am accused of “being defensive” or “claiming victimhood”. No. I am being honest. You can choose whether to believe me or not.

It is important to interrogate notions of masculinity. I am a reporter, not an activist. Yes, I am good friends with many of my interviewees, and some I do consider my brothers; I am also good friends with several of their partners. Recently, a transman’s partner ran away from home, ending a ten-year relationship after he beat her brutally. Everyone in the community is aware of the case.

Cismen do cruel things; so do transmen. Ciswomen do cruel things; so do transwomen. An honest book looks at all of this.

A book cannot be called transphobic because it speaks about surgeries. Surgery and medical transition cannot be ignored in a book about transpeople. And there are several layers to surgery – the pressure to undergo medical transition, the government’s insistence on it, doctors’ lack of expertise, hospitals’ greed – all of which feature in the discussion, as do the trans community’s own prejudices with regard to surgery.

A work of literature is not activism, and reportage cannot be pamphleteering. Which is why, sometimes, one uses stylistic devices such as quoting an interviewee’s words as part of the text. For instance, only the underlined section of the following extract has been used as a screenshot in Semmalar’s piece, and he introduces it with: “And then she places her sixth sense on an unnamed watchman and tries to displace her own transphobic lens onto him.”

I met him at a party for transmen and their partners. He told me he was suicidal. Counselling didn’t help. Two days earlier, he had gone to the terrace of his apartment complex. He had stood on the parapet, holding on to the water tank. For a few exhilarating seconds, he felt he was flying. He would count up to thirty, he decided. If someone happened to walk into his view, it would mean someone was listening. It would mean he mattered. He would climb back down. If no one walked into his view, it would mean the world didn’t care about him. Seconds before he would have jumped, the watchman blew his whistle. A stray dog shot out of the gate, followed by the watchman. He did not jump. If the watchman had looked up, he would have seen a girl in tears, not a boy in depression. Did he decide not to jump because the watchman and the dog were signals from god? Or had he latched on to a whistle and a canine because he didn’t want to jump? When he stepped off the parapet, he was not sure whether he was grateful or resentful. He was still breathing. In a body he saw as a trap. ‘Next time, if there’s nobody,’ he said, and made a gesture, swiping his hand past his throat. He smiled.

Semmalar adds: “And then wonders why Living Smile Vidya doesn’t share the same sixth sense when she meets a person who was not identified as a trans man at that time!”

This was not criticism of Vidya’s perceptiveness. I was simply surprised that transwomen did not immediately identify transmen. I am also examining my own preconceived notions of transpeople’s ability to identify or accept each other. I thought highly of Vidya’s autobiography and gifted it to three people I know, including two transmen, and both told me they found it “very similar, yet very different” to their own lives. I was also struck that they used the same phrase to describe the book.

- Poverty porn:

Semmalar writes:

“The author would put Levis Strauss to shame with her anthropological study of dosa and poverty. She says this person never went hungry, and yet pulls out a theory about the thickness of dosa and poverty at his house. Dominant caste researchers routinely access the homes of marginalised people to narrativise their own prejudices, all the while maintaining the privacy of their own households and families.”

There is much presumption here. Semmalar suggests I’m a “dominant caste researcher”, and implies I am among those who have “maintained the privacy of their own households and families.”

For the record, the transman mentioned here is a friend. I have no need to defend myself because the accusation is laughable. We have had multiple conversations about his family’s circumstances, and he approved every word I have written, which I translated verbally to him myself.

- Attempts to saffronise trans communities:

In the review, Gee Imaan Semmalar claims:

At a time when trans, gender non conforming and intersex communities in India are putting out statements against saffronisation of our representations and politics, the author imposes a Hinduised past on us throughout the book. She begins the book with a reference to Shikhandi, gives a Hinduised introduction to Manipur through the myth of Arjuna-Chitrangada, which the trans communities who lent their voices to the book have strongly protested as an erasure of their indigenous histories.

Shikhandi is part of mythology. As I wrote in a Facebook post on this issue, embedded below, “Invisible Men begins with the story of Amba and Shikhandi. It looks at Brihannala and Aravan, Mohini and Ayyappa. It fascinates me that the Mahabharata has so much gender fluidity and gender transition. My book also looks at Greek mythology, Nordic mythology, Andean mythology, gender roles in Shakespeare, Tagore’s Chitrangada, Plato’s Symposium, and other literature.”

Yes, I do consider The Mahabharata literature, and not a religious text. I have made this clear in the book too.

In another post, I wrote: “Mythology, fiction, and theories by philosophers have also been used in the book. None of these is claimed as fact, as should be evident from the words ‘myth’, ‘fiction’, and ‘theory’.”

I have also posted:

“Of course I don’t think Meitei people are Hindus. I don’t think Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Buddhists, Sindhis, Mormons, Scientologists or Atheists are Hindus either. Nor do I think any of the above, Hindus included, are worshippers of the Olympians or Pachamama or Ra or Thor.

In fact, all sections which deal with mythology are italicised unless they appear in chapters of their own.

All this would be evident if people read the book before spewing venom.”

This ought to answer Semmalar’s question on why the book “has major sections in italics which makes no editorial sense”. The italics are used in recounting myths and short anecdotes in the book.

I have been accused of being “defensive” for refusing to “apologise” to people who have drawn conclusions about the book without reading it, or – as this piece will prove – by misreading it. But when unfounded accusations are made, one must defend oneself.

The piece also says:

“The author at one point wonders whether “another category of neither-man-nor-woman” (apart from trans women) were waiting for a mythical Ram to return from a mythical forest for 14 mythical years! Once again, she sets aside trans men as being not men – this is a fundamental form of transphobia.”

As evidence, this is offered:

“Were there only transwomen in Ayodhya, who were not-men-notwomen? Or were they themselves guilty of the same oversight, to atone for which Rama swore he would protect them for eternity? In fostering this story down the generations, had they forgotten about another category of neitherman-nor-woman? Were there no transmen in Ayodhya? Or did they stand waiting too, ghosts to the very people who were ghosts to Rama?”

This is from a section which is excerpted in Reader’s Digest. The section begins: “This story cannot be found in most versions of the Ramayana—not Valmiki’s, not Kambar’s, not Tulsidas’s—but it is sacred to the thirunangai tradition.” Several transwomen – all of whom I am happy to name – have told me about this story. And it is also recounted in Living Smile Vidya’s memoir.

Given what happened with A. K. Ramanujan’s essay on multiple Ramayanas, and Vidya’s own declared politics, I’m surprised my mentioning the Ramayana is seen as attempted saffronisation.

As for the “transphobia”, Semmalar’s essay leaves this out, and I have underlined the operative line:

Every man, woman and child returned home. As the crowd began to disperse, Rama, Lakshmana and Sita walked into the forest. They did not notice that some people stayed behind. They saw them again, thirteen years later, still waiting. They loved Rama, but they did not consider themselves men, women or children. They were the hijras of Ayodhya.

I turn to the wisdom of Blackadder to illustrate the importance of context. For those who don’t have 2 minutes and 46 seconds to spare, please watch the video from 55 seconds to 1 minute and 15 seconds, less time than it takes to compose a two-sentence tweet:

- Violent nationalist fantasies:

This section contains yet another loaded statement, and several presumptions: “Apart from the attempt to Hinduise the history of Manipur, she writes a chapter titled, Why didn’t the Indian Army want to search me? In this chapter, a Kashmiri trans man says nothing close to the violently nationalist fantasy imposed on his narrative by the author.”

Semmalar adds: “This atrocious title is not some ignorant blunder by the author because in the same book, there is an extremely troubling account by a trans man from Manipur about body searches by army personnel while travelling by road.”

This chapter is about a transman from Kashmir, who spoke of how, as a child, he would wonder why his brothers and cousins accompanied their fathers to the fields on order of the Indian Army, but the personnel never wanted him to come along.

He did speak the words in the title. We have had several long conversations, in person and on the phone. Not every word we spoke is in the book. He approved the title, along with the text. He, too, has reached out to me since the trolling began, and though he is not out as a transman, he offered to interact with journalists I trust, on my behalf, or send a clarification.

I don’t think this is necessary. I will not put someone at risk to prove my credibility. The reader can choose what to believe. Here is a more detailed post that ought to show my account was not violent, nationalist, or fantastical.

- Brahminism

This section is largely a series of personal attacks, made on presumption.

Semmalar writes: “There is an entire chapter devoted to three cis Brahmin women saviours (the author, A Mangai, Mina Swaminathan) talking about trans men and our bodies in our absence.”

To begin with, none of these three women – including me – has been identified as either a Brahmin or a saviour. For the record, my family is of mixed ethnicity – not that it should matter. A screenshot of a joke I had shared with a friend on Twitter – an inside joke which refers to our days playing NRIs on a spoof radio show – has been doing the rounds as evidence of my caste. But if I’m not “caste-privileged”, I would be assigned another label that purports to undermine my credibility.

There is a chapter titled “Saviour” in the book, which has nothing to do with the three women Semmalar refers to as “saviours”.

The transman performer who is discussed in Voicing Silence was told of every exchange. I did translate every word into Tamil for him, and it was published with his approval.

Semmalar writes: “The chapter ends with them discussing his plans for bottom surgery and how he doesn’t earn enough.”

This conversation, too, was narrated to the transman, who had no objection to my writing it. He and Ms. Mina Swaminathan share a very close bond, and I am sure it would upset him greatly to know she was being spoken of in such terms as the “review” contains.

It is important to emphasise here that these conversations, about his surgery, happened some time ago. I have not discussed, and will not discuss, whether the transman in question eventually had his surgery. Very few of my interviewees asked that I share details of their surgeries. As all my interviewees would know, I asked few questions, and essentially told them they could talk to me about anything they wanted me to write in the book, and could withdraw their stories right up to the time of printing.

It ought to be apparent to anyone reading the book that the accusation of my “treating” my interviewees as “subjects of a study” is ridiculous.

The personal attacks continue when my veganism is conflated with Brahminism.

Among the first barbs is this: “If the author would like to make a career move, she must apply to be part of the BJP government’s district screening committees that are to ascertain and hand out transgender certificates.”

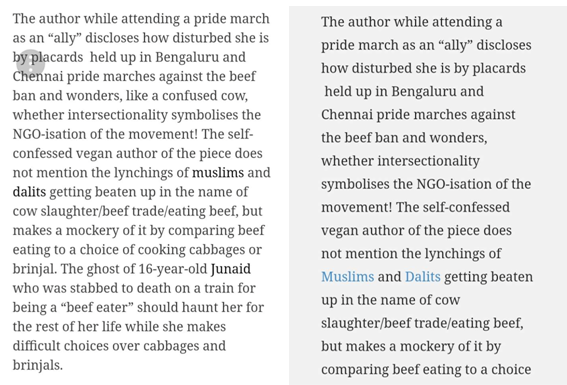

I was referred to as being “like a confused cow” in an earlier published version of the article, a simile which was later removed.

I would respect anyone who stuck by one’s convictions, however nasty or cruel they are; or, if those convictions have changed, acknowledged that they were once held. Why was the simile surreptitiously removed?

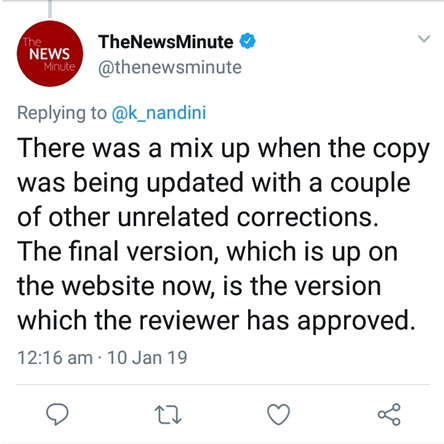

When I posted this on Twitter, The News Minute had this to offer:

Courtesy: Twitter

Sure, but then isn’t it standard journalistic practice to acknowledge when an error has been made? Or at least throw in a vague “This article has been updated to correct errors” or even “This article has been updated”? So, why does the piece end with:

.png)

Screenshot from Gee Imaan Semmalar's piece on The News Minute

I do wonder what the "mix up" was. Was there another piece on a genuinely confused cow? Or was it an Autocorrect error?

While giving me lessons in feminism, perhaps the writer could have paused to consider the misogynistic implications of comparing me to a cow.

As for Semmalar’s description of me as “self-confessed vegan”, that is a loaded statement too. It is not a “confession”. It is my identity. I am passionate about animal rights, and I love every animal, bird, insect, and germ on this planet. I believe the people who take pleasure in electrocuting mosquitoes are psychopaths.

I did not grow up vegan, or even vegetarian. I began to give up animal products from when I was twelve years old, and finally went vegan a few years ago. I am ashamed of my own animal-eating days. I am ashamed of having worn silk and used leather shoes. I am ashamed of having consumed milk that was produced for calves.

And I am haunted by plenty of ghosts – the ghost of every animal I ate, the ghost of every calf that died so I could steal his or her mother’s milk, the ghost of every bee that was burnt so I could consume, with my morning tea, the honey s/he spent a lifetime producing.

The principle behind veganism is the notion that animals have as much of a right to life as humans do – I do not believe humans should be lynched to protect animals; and I do not believe animals should be lynched to satiate human appetites. Doesn’t the ghost of the calf that was lynched in Kerala to protest the beef ban haunt all those who carry those horrific placards?

Any vegan – or scientist, or economist, or Googler – could tell you that the dairy, meat, and leather industries feed into each other. Veganism is the practice of eschewing all use of animals to serve human ends, in accordance with the belief that all life is equal. Is that the popularly-held notion of Brahminism?

- Sympathy porn:

The News Minute article states:

In his own voice in the book, Kiran comes across as a prominent disability rights and trans rights activist from an Adivasi community. And that’s how we know him – as an indomitable and proud brother who has won the Karnataka State Award for his amazing work in disability rights activism. But the author places a victim narrative on him and blames his parents for their “failure” of not administering polio vaccines. This is an atrocious accusation that erases the structural exclusions in healthcare Adivasi communities face. Throughout the book, the author cries into the night about our trauma, with a pillow as the only audience for her Stanislavskian acting techniques.

The section which Gee Imaan Semmalar offers as proof for these conclusions reads (emphasis through underlining is mine):

As we drove away, waving goodbye to Kiran and Kavya, I remembered being administered the polio vaccine orally. My last dose had been when I was five years old. It was bitter. It was not a mandatory vaccine at the time, and there were educated people in metropolises who did not bother vaccinating their children. I thought of Kiran, growing up on the outskirts of a forest, running and playing in childhood, before his legs were rendered limp by his parents’ failure to administer six bitter spoonfuls of vaccine. How hopeful he must have felt that this could be corrected by surgery. How much the doctor’s final diagnosis must have hurt.

Isn’t the implication of the underlined portions precisely that Adivasi communities have no access to healthcare? I do not “blame” Kiran’s parents, a literal interpretation of “parents’ failure”. It is obvious what the reason for this failure to administer the vaccine is – lack of awareness, from lack of access.

It is rather easy to believe the worst of anyone.

And it is perhaps this belief that allows someone to mock me for crying into my pillow, and dismiss genuine fear or grief as a display of “Stanislavskian acting techniques”. I prefer to attribute the mockery to misunderstanding than to bullying.

- Necrophilia

The piece reads: “Her curiosity around our bodies and our “vestigial uterus” continues in a sick show of necrophilia even after our violent deaths on operating tables of inept medical care professionals.”

This is a distasteful and unfounded allegation. It was an account of a hospital's callousness in botching the surgery of a transman. I am not "curious" about bodies. I do have a problem with hospitals and the medical infrastructure exploiting dysphoria, and the point of recounting this incident was to highlight that. I do not see how one can ascribe such ugly motivations to someone whom one does not even know, and I wish Semmalar had not said what he did.

- Dehumanisation:

Semmalar writes:

There is an entire page [pg 22] when multiple trans people are named as kothi, chela 1 , chela 2 etc rather than by name. On the same page, the author refers to a trans person multiple times as “it”, claiming that it’s the translation of adhu from Tamil. But anyone familiar with non-Brahmanised Tamil would know that it is used regularly to refer to people. The author herself in the footnote cleverly says “she” would be the politically correct term but that unnamed trans women (a device used to blame and hide behind the very community she dehumanises) have told her about rituals that are required for a kothi to become a thirunangai and “earn the female pronoun”. She hence problematically justifies using “it” instead of she/they as pronouns for the trans person in question.

If only he had turned to Page 21, he would have seen that this is from the script of a play:

Unsettling Memories, Part 5

Directed by A. Mangai

Reet

Young kothi comes into the jama’at. He touches the feet of the senior transwomen, saying, ‘Paon padti.’ They bless him with ‘Jeete raho.’

The script was devised by the members of Kannaadi Kalaikkuzhu, and written by A. Mangai. Mangai, who read my English translation, suggested that I translate “adhu” into “she”. But I explained that I wanted to translate “adhu” as “it” because of what these transwomen – all of whom I can name, but figured it was irrelevant since most readers would not know them and the sentence (and book, for that matter) was long enough without more names – had told me. In fact, this conversation, about earning one’s pronoun, is on video, as part of the documentary I shot in 2006.

The fact that Semmalar has not read the book carefully is evidenced by the erroneous:

The same person is mentioned again in the book [pg 182] as asking, when not allowed to carry the author’s luggage, “Is it because I am not yet a ladies? But think of me as a ladies.”

First, it was not the same person, since the play was devised in 2003-04, and the kothi in the play was fictitious.

The section where the real-life adoptee is mentioned reads:

When I was making my documentary on transwomen back in 2006, I had had a conversation with a young kothi, who had just been adopted by Priya and was yet to be allowed to grow his hair. I was asked to call him by his male name and use male pronouns. He carried the transwomen’s luggage, and had tried to persuade me to let him carry mine. We sat outside the Koovagam temple, on mats. In the quiet hum of people settling down to sleep, of prospective clients negotiating with thirunangai sex workers, he asked me if he could touch my hair, which at the time reached my hips. I laughed, but refused. ‘Is it because I’m not yet a “ladies”?’ he asked. ‘But think of me as “ladies”.’

Semmalar writes: Why the author would misgender and dehumanise a person, who is clearly female identified, and place the decision on unnamed trans women who apparently instructed her to do so, is incomprehensible.

I have named Priya, have I not?

As another example of “dehumanising”, Gee Imaan Semmalar offers:

The author’s attitude to her participants in the book is apparent when she describes a person with an intersex variation as a “golden goose” who had been through many forms of discrimination. She uses the archaic term of “hermaphroditism” to describe his variation – something that intersex activists globally have condemned as a term of reference.

The person I interviewed here is someone with whom I have a great rapport. We have joked about his being the “golden goose” for the book. He used the term “hermaphroditism” to describe his condition, and so did his doctor, whom I interviewed too. Like everyone else, he read the chapter, requested changes, and approved of the final copy.

I’ve been asked why I did not share the “final manuscript” with my interviewees. First, this is never done. Even quote approval is rarely sought. I did make it a point to seek quote approval, because these were not simply interviews, but narratives of lives. Second, I could not share the entire manuscript as soon as it was ready because it would be a breach of privacy since most interviewees wanted changes after they saw the copy in black and white. Third, and perhaps most important, the manuscript can only be shared with a co-author. I do not have a co-author for the book. It is a collaborative effort, in that I made sure my guides, interpreters, translators, and cab drivers were transmen, in addition to my reporting their stories verbatim. But the journey of writing the book is my own.

The book is not written for profit. I have disbursed all the money I have received from my publishers to my interviewees, prioritising them by their current income as well as scale of contribution to the book. This is one of the reasons I was particularly upset by a campaign to pirate my book and share a PDF so that no one would have to pay to read it. The kind of people who pirate books are not the kind who buy them, and so these are not lost sales.

But they allow people to claim to have the book, quote chunks of text, and write fake reviews on Amazon, which you can see here. The ones who did not choose anonymity have the same names as the Twitter handles and Facebook accounts that most frequently trolled me.

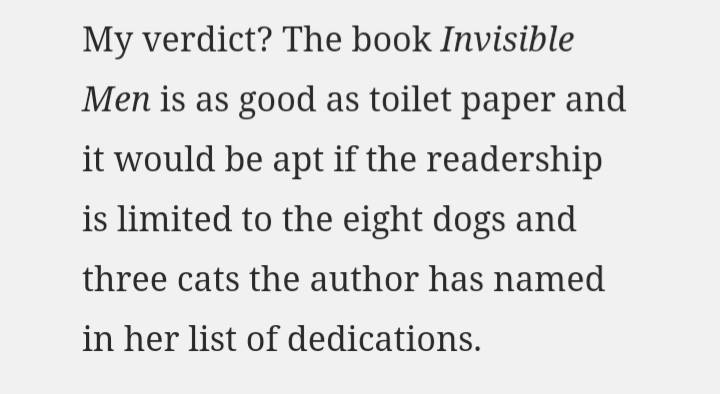

The vitriol in these “reviews” is in keeping with the style of this final note in the News Minute piece:

The dedication a writer puts down is among few truly personal sections in a book, and surely such a statement is bad form?

I do understand that hurt and anger can make one lash out. I also understand that some extrapolations could be because journalists have let trans interviewees down in the past. And I understand that once one has raged against a book without reading it, it becomes important to find something in the book to justify that rage. However, that is not a review. It is a rant.

It’s a choice one makes to either overwhelm someone with so many tags that one cannot possibly respond individually, or to confront someone with assumptions and extrapolations, or to engage with someone after reading the work in context.

It’s a pity people who brand themselves activists have so much rage and so little faith that they should resort to piracy based on, as I said, extrapolations and assumptions. I do hope better sense prevails, because – though I cannot pay my interviewees for their time in advance, since that would become a “paid interview” and lose credibility – I can pay my interviewees from royalties, and that is what I have been doing.

The piracy was not the worst thing that happened to me in the last week. My number has apparently been shared on several WhatsApp groups, and I began to receive threatening and abusive phone calls in various languages. I eventually set my phone to auto-record calls, after switching it off for several days. Here’s an account of what happened.

When I posted it on Twitter, this is what happened:

I haven’t been reading all the tweets I’m tagged in, since they run into thousands, but one asked, “Do you believe all transpeople are illiterate?”

If I did, I would not have sent out copies to all the transpeople I interviewed.

But when I saw pictures of the copy I had gifted All Manipur Nupi-Maanbi Association set on fire by MSAD, SSUM, ETA and AMANA, being shared and celebrated, complete with tags and jibes, I realised I do believe one thing: No one who has ever loved a book could burn another.

NOTE: Unlike my book, this article may be reproduced or uploaded in its entirety on any website.

Also, if anyone from The News Minute is reading this, could you please ensure the photograph you’ve used without my permission is credited to ‘Vinay Aravind’? Thank you.

Leave a Reply